Unlikely Leaders: Lessons from “Today I Saw a Revolution”

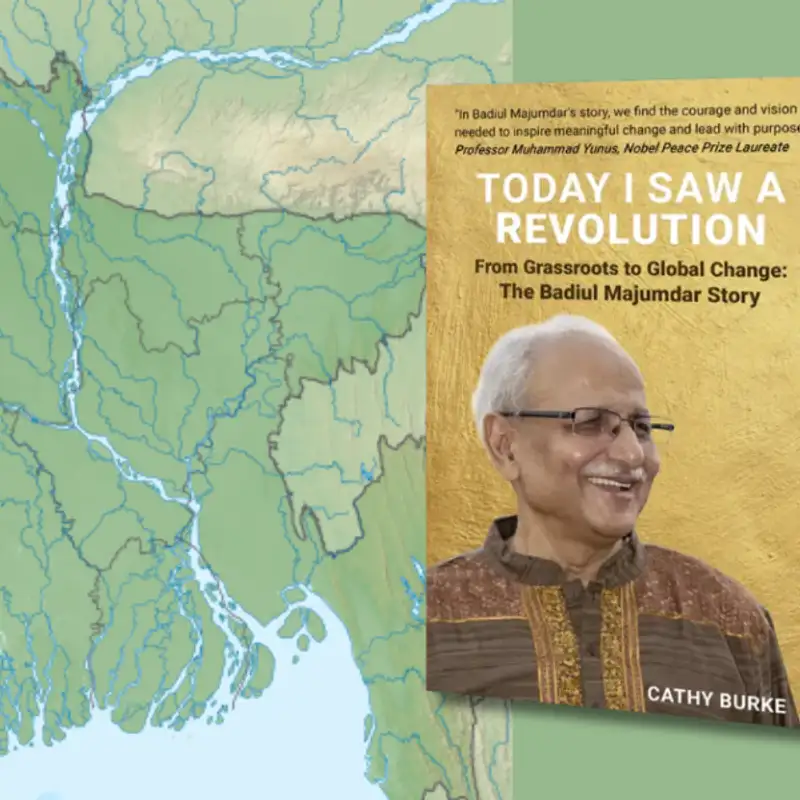

Charlotte Tate: From the Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs at Middlebury College, this is New Frontiers. I’m Charlotte Tate, the Center’s associate director. In this episode, author Cathy Burke joins Mark Williams to discuss her new book—Today I Saw a Revolution. The book chronicles the work of anti-hunger activist Dr. Badeel Majúmdar, the grassroots movement he helped create, and the lessons his approach to achieving change can teach us about leadership, power, and how to wield it.

Mark Williams: Cathy Burke is a global leadership expert and former CEO, who spent two decades with the Hunger Project. During that time, she worked to develop leadership at scale and communities across Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. She's the author of several books and her latest, Today I Saw a Revolution, tells us the story of a transformative grassroots movement in Bangladesh. At the core of this book is Dr. Badeel Majúmdar, a man who became central to ending hunger in Bangladesh and whose life work, Cathy writes, and here I'll quote, “is one of the most remarkable untold stories in the global fight against hunger and inequality.” In the process of telling his story, the book challenges conventional views on how we think about leadership, how we think about power, and how we think about achieving and affecting change. Cathy Burke, welcome to New Frontiers.

Cathy Burke: Thanks for having me.

Mark Williams: Why don't we dive right in. For 20 years you served as CEO and then Global Vice President of the Hunger Project, Australia. For listeners who don't know, can you explain what the Hunger Project is and what it does?

Cathy Burke: It's an international development organization that works across more than 20 countries, and its mission is to end hunger. What makes it particularly interesting is that there's loads of ways you can try and end hunger. You could do food drops, you could set up food kitchens. There's a myriad of ways that you could do it. But how the Hunger Project tackled it is that it wanted to end hunger sustainably so that it wasn't a continual need to deliver some sort of aid. But the primary premise, which was what really attracted me to them, is this understanding that the people who live in conditions of hunger aren't the problem, and we've been conditioned to see people living in hunger and poverty as some sort of problem to fix. You know, if we just gave more food. We see them as this like a billion mouths to feed, this sort of huge mountain that we need to kind of press and sort of put some force against to try and move it in some small way, which will never happen with that sort of mindset or frame of mind around it.

And what the Hunger Project does is really see that the hungry themselves live in absolute terrible conditions, but they aren't the problem. They're the solution. So they're the solution. They've got the most at stake and they have the biggest energy to bring to solving this problem. And so, how do we unlock their leadership? How do we think about power differently? Who gets included that's not currently included? The organization was then run from a completely different set of questions other than how many more mouths can we feed? Or who's to blame or whatever, really to unlock that solidarity, that leadership, that vision of the poor themselves. And it really inspired me when I first heard about it. And it's been going for nearly 50 years. I was thinking about this last night in preparation for today, and I thought, wow, it's been going for nearly 50 years. But the ideas around it still feel really new and fresh.

Mark Williams: So what led you to becoming involved in this work initially? Presumably you were doing something else before you became active in Project Hunger. How did you become involved in this type of work and how did this eventually lead you to meet the man that you write the book about?

Cathy Burke: Well I'll skim over my wildly misspent youth, Mark, of running a nightclub. I used to tour punk bands and still managed to go to uni to get a degree. But there was always some call or broader yearning within me to do something that mattered because so much seemed really meaningless, and not that I had a particularly nihilistic streak, although maybe that's what did draw me to punk music. But I really grappled with why am I here? Is it just to do more of what I'm doing, like live, consume, and die basically? And I used to think there was something sort of wrong with me, if you like. And now I understand it in a much broader context of this is the sort of growth that questions, that all of us need to face at some point in our life. And I guess I just faced mine in my twenties. And I found my life partner quite young. We had a child quite young, and it was actually when I was holding her and looking into her eyes and really thinking about not just how much I love her, but how much every parent holding their child loves theirs. And how unfair it was that so many died of the common cold, died of diarrhea through no fault of their own.

That–when a friend of mine told me about the Hunger Project, and at that time I had been working for a senator in my home state– told me about the organization, I got involved and I volunteered for five years. I went to Ethiopia in a really seminal, changing confrontation with hunger in 1992, not that long after the Live Aid famine, I guess, of the eighties. And I had that point on the path where you get to choose and I thought I have to do something about this, even though I didn't have a degree in international relations. I lived in Perth, which is the most remote city in the world. So it was this whole identity, well, what can I do, I'm only one person? But I just thought–it was that African proverb, like, I build the road and the road builds me–so it was in making that choice to step up in some way, however small, shaped me into becoming the leader that I became. And so for five years, I just volunteered like a crazy person and then eventually went on staff and then became the CEO here in Australia. And then Global Vice President.

Mark Williams: That's a remarkable journey, and I can relate to some of the youthful adventures that you allude to. There are some in my past as well. Now, your book focuses on Dr. BadiulMajúmdar, and he is a Bangladeshi economist. He becomes a leading human rights figure in his country, and so I'm curious about this man and what you saw in him, his journey so to speak, that sort of compelled you to want to write about it.

Cathy Burke: I met Badeel, I think in 1997. And I don't know what it was. We both clicked. So there is something about when you are working in a global organization, that was primarily headquartered in New York, and you have these like colonial outliers sort of heading into New York. So, there was like lalita from India, me, him from Bangladesh. We’d hovel around. We're the only ones drinking hot tea. And so we were like the naughty children in the back of the bus in some ways. We just clicked and I was just amazed at what he was doing, the breadth of his vision that a country that Henry Kissinger had said, like 20 or so years earlier, was a basket case. The vision that he held for a country that pretty much everyone had given up on was so inspiring, Mark. And I had the chance to then visit there for the first time in 1998, and then to see this man so loved and sitting in a village surrounded by women. The way he brought such deep listening, curiosity, but this real fierce belief in something else was possible for his country and his belief in the most marginalized, the poorest of the poor.

So, it was my first time in Bangladesh, which, especially at that time, you'd walk through villages and you would literally not see one woman. There were men everywhere. You'd see cows. You'd see rice patties. You'd see people going past on their push bikes. But the women were very much cloistered. You may see one who was surrounded by other men. It was a very segregated society in rural communities. Women, highly subjugated, highly marginalized, very little access to education, not able to really make decisions for themselves. Child marriage. So very often you'd see 13, 14-year-old girls with a young family. So that was hugely confronting. And yet seeing this man who was not fazed by that. He was energized by his vision for his people. And he engaged the grassroots in a way that created such solidarity that I hadn't really seen that level of solidarity before, and awoke in them their own leadership and their own agency, their own fire, for them to make the changes that needed to happen. And so I've only seen that more and more over the years, and he's just taught me so much about leadership.

And I've seen the difficulties he's gone through. So, the powers that be that he upset, the death threats that he's had, the tremendous strain and pressure on his own life, I've seen that side too.

Mark Williams: Let me clarify one point and then ask another slightly different question. You met him not in Bangladesh. You got to know him in Bangladesh perhaps, but you met him elsewhere.

Cathy Burke: Yeah, I met him in New York City. He’s actually an American citizen now. So when he got a university scholarship in his early twenties to study in America. This is the other thing about Badeel. He was born just before partition, just after the Bengali famine. He lived, he grew up in the most immense poverty, Mark. He knew hunger, he knew lack.

But education was his way out, and he got a scholarship to America and ended up living there for nearly 30 years. And he ended up becoming a professor of finance and economics at universities like Claremont University and Case Western University and others. He was very much steeped in traditional economics. But it was really returning home to leverage the energy and the power of the poor that really changed the way that he even thought about economics in the middle part of his life.

Mark Williams: So at some point he left the path of being a typical academic, someone like me, and he went on become to a leading figure in his country for human rights and for ending poverty. You had mentioned earlier, in passing, about death threats that he might have received and I'm curious about why would an economist be threatened with death? What was the source of these troubles that he was having?

Cathy Burke: Well at this point, he wasn't an economist at this point. He was the leader of Bangladesh's largest grassroots movement for justice, for empowerment, for the end of poverty. He was a fearless, and is a fearless, speaker against corruption, which was absolutely endemic.

Bangladesh was number one on the international corruption index as held by Transparency International. So here you have this man who did leave a beautiful life in America. Like he really had it all. He had tenure, he had a sweet, sweet life. He had children, he had a beautiful wife.

But yet again this yearning, Mark, of like, is this it? I left my country on the eve of the war against Pakistan’s liberation and is my life just about me living an even nicer life, and then that's it? There was always this calling, that eventually I will go home and work out what is the difference that I can make.

And many of us think that even if we don't think to go home, we think, oh, at some point I'll try and make a difference. And a lot of us just get stuck in that sort of track that we're on. And he managed to pull out of it and go back to Bangladesh. And so it was through that work that he did that was not popular. It was not done for a man of his class as well–to be so vocal against the powers that be and also such a force within villages and communities.

Mark Williams: It sounds to me as if it wasn’t his academic career that led to the death threats, it was more political influence. And once he got into the political realm, where enemies could be made and interests were stronger and people wanted to protect whatever interests that might have been threatened by his activism, that was at the root of his problems.

Well, in August 2024, Bangladesh experienced what people have called the monsoon revolution. And this is a type of, for lack of a better expression, a political earthquake that was created by student led mass uprising. And that uprising ultimately forced the Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, to resign. And I'm wondering if you could tell us a little bit about this uprising itself and perhaps how the grassroots work that Badeel had been doing over the years might have contributed to that incredible political moment.

Cathy Burke: So the monsoon revolution in August last year was started by the students, fomented by the students, as you say, and it initially began because they were protesting what they felt was an unfair exclusion from university positions government held positions for those ancestors of the freedom fighters in the liberation war, which 50-plus years later cut out a lot of people. And there was a lot of nepotism and things involved in these sorts of places. There was immediate sort of police and government hardline response to that, but more and more students gathered in Dhaka, then around the country. And then over the ensuing days just normal people joined them on the streets. And millions of people were involved. And the students’ demands moved from changing this particular way of quota system into let's get rid of Sheikh Hasina, who had been in power for about 15 years at that time, was incredibly dictatorial.

As it turned out, Mark, there were horrific, underground jails and all sorts of things where people she didn't like basically just had been taken and just dumped there, out of sight. Some for years. There had been so many extra judicial killings over the years. The country had become a kleptocracy. So, it was the government that money could buy. And she was the leader of the Awami League. And in the end, even though many people lost their lives, she ended up fleeing. And many, many of the ministers and others fled to India.

And the young people then demanded that Nobel prize winner Mohammed Yunus take over with the interim government leader, which he did. And he, Yunus, then appointed Badeel to overhaul the electoral commission, to help restore democracy.

Since the 90s Badeel had created this huge movement of hundreds of thousands of young people training up their leadership, because he genuinely had a vision for the energy and the potency that young people could bring in their villages and communities. So he'd worked really diligently. And because they had the internet cut off for nearly two weeks, he didn't know. It was maybe a month later when he found out who leaders of the uprising were. Many of them were people that had been in youth ending hunger.

Mark Williams: As one would imagine when the mass movement mobilized against the Bangladeshi regime, political uncertainties and insecurities within the country spiked too. So much so in fact, that Cathy grew concerned for her colleague's safety and wellbeing.

Cathy Burke: I was in Portugal at the time, just finishing the book, and then it was like, what's coming out of Bangladesh? Then he went off the air and I couldn't get to him. And is he all right? Is he alive? Like what's happening? Because he was classically someone who could have just been dragged off the street himself and we would never have seen him again.

Mark Williams: But Badeel wasn't carted off and tossed into a cell. Instead, the regime fell. Pushed over by a movement whose very leaders he’d helped inspire and train.

Could we circle back and sort of drill down on the work that Badeel was actually doing that brought him to this level of prominence that you're referring to? How did he get started? Once he leaves the United States, he comes back to his country. What types of things did he engage in that were instrumental in creating the anti-hunger movement?

Cathy Burke: When Badeel came back from America, he realized that he needed to reacquaint himself with his country again. So he spent nearly a year actually traveling the country, meeting people, spending time in villages, communities. He was also looking for work and had some other jobs as well. So he'd spend like a week in this part of the country, then back to Dhaka, then a week somewhere else. And he really went, Mark, to learn to understand what the country was now versus what he thought it was.

And what he saw was that the great promise that the Liberation War had offered this proud nation that had flung off the mighty Pakistani army, had this huge vision for their country in the early 90s, that it seems to have vanished. People were resigned, they felt defeated that this is gonna be as good as it gets, and how it is right now is not very good. So he came to a real awareness that unless this fundamental understanding of what was possible for Bangladesh was changed, then nothing would change.

I don't even think the word mindset was even used then. But that's what he was talking about, this sort of feeling of fatalism, despair, resignation.

Mark Williams: So how did he propose to change this mindset?

Cathy Burke: So he devised an idea to create a workshop, which he called the Vision, Commitment and Action Workshop, the VCA, as it’s called. He thought, let's have people engage with what they're thinking about their future. And so he co-created it with his colleague John Coonrod in New York. He trialed it in Dhaka.

And for everyone, something shifted, particularly when they got to the vision part of the exercise. This ability to actually give yourself some space to think about how something might be versus get stuck on just how it is.

It seemed to work for the middle class in Dhaka, but it was really when it then rolled out to the villages and he's sitting in a village with, at this time, mostly men who are daily wage laborers. People are hungry. And you're talking about these concepts of what could my country look like? What could my life look like? Why am I poor? It's almost like a participatory research way of thinking about things. And what could I do and what can we do as a community?

And I've sat through so many of these, Mark, and you see people weep, very softly sometimes. With their eyes closed as they're going through this vision process. And when they start to think about, as they start to imagine, yeah, like clean water and my daughter gets to finish her education and we get to do this and that, people are very moved by it.

And then it's about we need to commit to it. You can't just have a vision. What are the actual actions we are gonna take that over time will get us to that vision? And so the VCA, as it's called, became like the cornerstone. So more than five million people have done it across Bangladesh. It's now spread to across all parts of Africa and different parts of the world as well. I've run it here in Australia; I’ve run it in different countries too.

One of the key elements of the VCA that the Badeel unlocked in people was that, yes, we have these huge problems and we live in this society that's very unfair. And yet, that doesn't mean to say I have no power in relation to that situation. And it was questioning my relationship to my power with regard to the circumstances I'm in that really created the liftoff for people to engage together collectively in village work, which is what ended up happening. So that became the foundation and upon which multiple other programs, mass leadership was then awakened around the country.

Mark Williams: Taking workshops nationwide that were only tested in one city can present tremendous financial and logistical challenges, even if, or better especially if that one city was the nation's capital. I asked Cathy to elaborate on how workshops like the ones she attended and saw Badeel leading, wound up going nationwide.

Cathy Burke: I've sat through many, and they're always in Bangla, so I have someone translating next to me. The interesting thing with Badeel, that economics professorship never left him. He was constantly looking at the principles of leverage. Constantly looking at how do I take myself out of the picture so I'm not a blocker, and how do we then mobilize countless others? So when he saw the VCA working so well, he can't lead them all. He'd have to have a huge budget to hire enough trainers to lead it, which he didn't have. So it's like, well I'll create this whole other program. And he trained up more than 200,000 volunteer leaders across villages, across Bangladesh, who then went into their community and led the VCA.

Mark Williams: As Cathy discovered, Badeel's aim wasn't just to call on Bangladeshis to start working on ways to solve their own problems with poverty, malnutrition, and so on. It also was a call for government accountability.

Cathy Burke: This is why Badeel had a two-pronged approach. How do we awaken this leadership and agency of the people? And how do we call the government to create this governance accountability piece? Because the government should be providing workable schools. They should be paying teacher salaries. There should be health clinics that people should go to. But a lot of these were being starved of funds through endemic corruption.

So calling the powers to be to account was the second prong of his approach. He set up a sister organization called Shujan to do it. And I love this too because it wasn't just like a pull yourselves up for your bootstraps, like gaslighting It was this is your life and your village. There's lots of things that are happening here, like just basic washing hands, sanitation stations, not marrying our children early. There's lots of stuff that we can actually do without extra money that would make life better, but we need to commit to that and then do that. Right? And poverty will not ever really move unless there's the government policy changes, accountability, proper governance that goes with it that you want in a democratic society. So he pulled those two levers.

Mark Williams: Can we talk a little bit more about this concept of mindset that you had mentioned earlier? Help us understand its centrality to the success of this movement.

Cathy Burke: It’s so important. Actually, my second book–Today I saw Revolution was my third book, Mark–but my second book, Lead In, is really understanding mindsets. Because I saw it everywhere in the field, across Africa, across India. And I remember when I was first young and starting off at the Hunger Project, I was told that mindset was key to ending hunger. And when you're standing in a village with a woman who's feeding herself one bowl of cooked rice with maybe some fried chilies on top, and that's all she'll eat all day. She's pregnant and she's got like three children, and you are hearing its mindset. I felt like, what the hell?

I guess because I had misunderstood mindset as more like positive thinking versus how the Hunger Project sees mindset. It's perfectly understandable and reasonable that if I was that woman in a village eating that one bowl of rice a day, I would feel that Allah has deserted me. I can't do anything. It's all hopeless. Where mindset comes in is, it's not asking her to think differently about her situation but to think differently about herself and her power in regard to that situation. And start to consider what could be done, what could be done in solidarity with others.

For instance, there's a woman that I write about called LiJu who was a woman like this, very poor, and went to a Hunger Project discussion, a VCA, talking about, you know, how we think about things. She joined what's called a self-help group that was 30 other women, would come together once a week, all poor like her, all to discuss their condition. But also to discuss what else could be possible. They would put aside a fistful of rice, Mark, dry rice each day into a small mound. They'd come to the meeting together. They'd pool the rice that would be sold, for some small amount of money, which would then be loaned to one woman who would then buy chickens in LaJu's case. And that was her start of some economic road out of poverty, which it ended up indeed being.

These were resources gathered amongst each other. These were not given to them. And that's a lot, that's an investment, a fistful of rice every day in the hope that something else is possible. It's pooling. It's seeing resourcefulness in a different way. It's really breaking out of a scarcity mindset that we have nothing. This is the power of thinking about ourselves in regard to our situation differently, including the belief that I can't do anything, I'm too small, I'm just a woman.

I’ve been in villages where there's one literate person and they're running like a free little classroom after the laboring in the field is done just to teach people some letters. It just became this movement of something else is possible, I guess. Mindset was the key driver to that. And the VCA, the vision, commitment, action workshop was the original tool to help people shift how they thought about their situation and to create a vision that something else might be possible.

Mark Williams: That’s really amazing.

Cathy Burke: It really is.

Mark Williams: Given the time that you've spent in rural Bangladesh, I'm sure you probably saw a number of people go on to become trusted leaders in their community, even though they themselves might have been illiterate or have been living in poverty. Do you think that outcomes like that can tell us anything useful about leadership itself? Where leadership actually comes from? How we can tap into those reservoirs of influence and power that because of mindset perhaps, we haven't done, to that time?

Cathy Burke: So my first book was called Unlikely Leaders–Lessons in Leadership from the Village Classroom, because it captures exactly that, Mark. There is a narrative around what leadership is and who gets to wield it that most of us don't fully examine.

What Badeel showed, and I've seen it across so many other countries where the Hunger Project's working, is that the possibility for leadership resides in all of us. I see it like an electricity current. The electricity can either be switched on or switched off. But the thread of electricity is always there, like in a light switch. And that's true for you. It's true for me. It's true for LiJu in that village.

And just a postscript to her, she started off really small with that fistful of rice. I met her once and then I caught up with her 20 years later and she had stopped 35 child marriages in her village. So no one would've looked at her, Mark, and thought, oh, she's a leader.

And I guess I resonate with that because no one would've looked at me and thought that either. You know, as an average student at school, certainly very average at university. I was a bit lost or whatever. I wasn't that fast track kind of, “Oh yeah. She's, she's the one.” Far from it. And this unlikelihood of leadership, I find it inspiring because, irrespective of your conditioning, your upbringing, your education, who you know, what gender you are, that thread of leadership is still there to be awakened.

And so for myself, I need to continue to take responsibility for keeping it awake And to activate it and unleash it in others to see who people are and can be. And to help them walk that journey as people have done for me. Badeel’s done that for me. He also saw something more in me and he's helped grow that in me as well. And I try to then hand that on to others.

Mark Williams: One of the things that I'm sort of curious about, Cathy, when you were conducting the research for your book, what is one of the most surprising or counterintuitive things that you came across? What were you not expecting to find as you were doing your research, that you did find?

Cathy Burke: I'd known and been very, very close to Badeel and his family for 25 plus years. But he was sacked when he went back to Bangladesh. So I hadn't fully got under the hood of that little drama until I was writing the book. But he went back to Bangladesh, a classic kind of American professional at the height of his powers. Thinking, “Oh, I'm gonna make a real difference here. They need me.” He worked for a functionary organization that was engaging in some corrupt business. Badeel called that out, spoke to the minister, was very naive and ended up getting sacked.

And that was a huge wake up call for him. Because he was like, “Okay, this whole dream of mine to make a difference is over and we are just gonna have to move back to America. I'm just gonna have to be a professor again.” And then fate intervened and he ended up meeting the leaders of the Hunger Project who happened to be in Bangladesh not long after that. And the rest is history. But this is a rocky road that he had.

Mark Williams: It wasn’t a linear progression from one triumph to the next.

Cathy Burke: No, not at all.

Mark Williams: Well, finally, what do you hope that listeners to this podcast and readers of your book, for example, what do you hope that they take away from the story that your book tells? And not just about Badeel, but about leadership? About what might be possible in their own life regardless of where they might be located?

Cathy Burke: Obviously, I want as many people to read it as possible. But I really want university or college students, as you call them, to read it. Even though it's a story of an 80-year-old man. He's like got the fire and the playfulness of a 20-year-old. And we live in unparalleled times. We do need a new vision for who we can be and a reminder that our resources and what we have to combat fascism, to combat climate changes, to deal with the complexity of AI, or whatever it is, that isn't just in the numbers in our bank balance or our position or title here or there–these external things that we measure. It's actually in the more invisible resourcefulness, our ability to partner, to rethink about our thinking, to create solidarity, to work on our own hopefulness for the future, which is also a mindset.

It's a reminder that, and this is particularly true for this book, that these things won't be solved quickly. But there is real power in committing yourself to something that may be long and something you may not ever see the end of in your own lifetime. And that this is true for Bangladesh and for Badeel. And yet it's still worthwhile showing up for it. So this idea that, I don't need to know how it's going to turn out, it's still the right thing that I need to be putting my energy toward in some way.

Ending hunger in Bangladesh was never a sure thing. And there is still hunger in Bangladesh; it's not like it fully ended or anything. But it was worth doing. And he spent 30 years of his life doing that.

And I just think being reminded that the tough things are tough and hard and then you die. And how glorious, how glorious to have put your shoulder to that wheel.

Mark Williams: Having lived a life well spent.

Cathy Burke: Absolutely.

Mark Williams: A combination of vision, as you mentioned, hope, but wedded with action. It sounds to me like you're also describing. And that combination of three things can help raise people up. It can help them to become animated. It can help them take charge of their destinies in their own locale to the extent they're able to control certain things. It's a wonderfully inspiring concept and I'm really happy that you wrote this book, and I'm glad that I've had the chance to speak with you about it. It's been a fascinating discussion. Thank you so much for visiting us here.

The book is called Today I Saw a Revolution. It’s published December 2024. The author is Cathy Burke, and you can pick up a copy from Amazon or your local bookstore.

Cathy Burke, thank you so much for visiting us here on New Frontiers. It's been a pleasure.

Cathy Burke: Thank you, Mark.